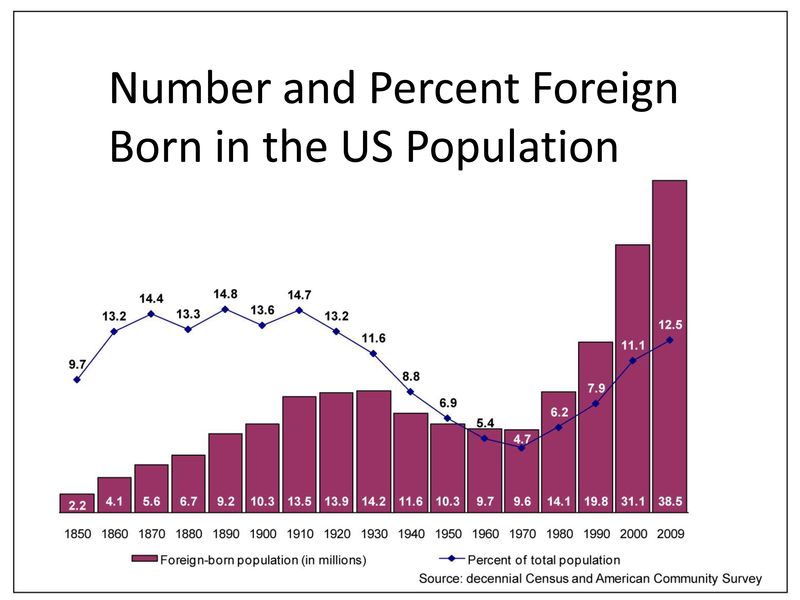

“We are approaching a new highpoint in the prevalence of US residents who were born outside the country.” This is part of a message on the Director’s Blog of the US Census Bureau website that is aimed at the marketing industry, at advertisers of goods and services, but we at CFHI believe it is also important information for current and future health professionals.

“We are approaching a new highpoint in the prevalence of US residents who were born outside the country.” This is part of a message on the Director’s Blog of the US Census Bureau website that is aimed at the marketing industry, at advertisers of goods and services, but we at CFHI believe it is also important information for current and future health professionals.

While the Census Bureau is providing this new data, none of the basic trends of an increasingly diverse population for the United States should be a surprise to us. Forward thinking health professionals and medical educators have seen the indications of these trends for many years. Health science students (including medical students, nursing students, and public health students) have not waited for courses to be developed by the data that is now beginning to be analyzed, but have taken the initiative to seek out medical electives and rotations that would give them first-hand experience of different cultures and the different ways people view health around the world.

With some 6,000 alumni of CFHI Global Health Immersion Programs to date, we hear over and over again from them how their CFHI experience gave them insight into the role that culture plays in health and healthcare. Tenny Lee, a 2010 CFHI Mexico alum, reports: “My experience in Mexico has given my medical career a foundation to help underserved communities and break though language and cultural barriers.” You can read more about her CFHI experience in her review posted on the website Great Nonprofits. The ability to competently serve a more widely diverse patient population will clearly become the expectation for health professionals, as we can see from the wealth of information that the US Census Bureau is releasing.

One of the most important data points released so far is that the Hispanic population of the US now exceeds 50 Million, a 43% increase since the last census as reported by CNN. And it is not just in border states in the south. The CNN article quotes demographer Jeffrey Passel at the Pew Hispanic Center as saying, “Previously, the Hispanic population was concentrated in eight or nine states; it is now spread throughout the country.”

One of the most important data points released so far is that the Hispanic population of the US now exceeds 50 Million, a 43% increase since the last census as reported by CNN. And it is not just in border states in the south. The CNN article quotes demographer Jeffrey Passel at the Pew Hispanic Center as saying, “Previously, the Hispanic population was concentrated in eight or nine states; it is now spread throughout the country.”

Medical schools, organizations, and institutions of higher learning have also recognized these trends, and CFHI has been happy to work with many of them to design specific programs. The Patient Advocacy Program at the Stanford Medical School began a program abroad with CFHI in 2007. The University of California at Davis has partnered with CHFI for over five years now to offer a Bi-National Health Quarter Abroad program for undergraduates in special arrangement with the Chicana/o Studies Department at UCD. Both of these programs also make use of CFHI’s built-in Spanish Language and Medical Spanish Instruction. Students are also living with host families so they are immersed into the culture during the program. Guided journaling and weekly meetings help students reflect and integrate what they are learning from their daily interactions. CFHI is also working with others, including Northwestern University, The Student National Medical Association (SNMA), -which you can read more about in an earlier posting– and the Public Health Institute in association with the Global Health Fellows Program. CFHI has been able to partner with each group and use our 20 years of experience working at the grassroots level in underserved communities abroad to design programs that meet specific learning objectives that are achieved in real life settings with the help of local health professionals who have the unique expertise of the local healthcare system and the best understanding of the local culture.

Jessica Brown, a 2010 CFHI Ecuador alum, pulls it all together in her reflection about her CFHI experience:

“… [I] learned a wealth of information about health that extended beyond the Reproductive realm.” Jessica goes on to say, “I learned a lot about Ecuador’s healthcare system by discussing health care access, education, socioeconomic class and ethnic background with my mentors and preceptors. I learned about how religion, education and customary social/cultural schools of thought (i.e. machismo) weigh heavily on Ecuador’s society, and individual minds; I saw how the cultural “way” dictated the population’s attitude towards healthcare, especially in Women’s Reproductive Health.

The moments that caused me to question belief systems in place within myself really stretched me beyond limits I never knew possible. And it is these reflections upon the state of health care in Quito that can broaden my understanding of client needs, beliefs and culture here in the states.”