Heads of State vow to “achieve social and health equity.” Students respectfully ask for more specifics.

Last week, Heads of State, Ministers, government representatives, and leaders of different sectors met in Rio de Janerio at the WHO World Conference on Social Determinants  of Health. (Writing and discussions about social determinants of health can often get lost in very academic and sterile sounding language, so it is important to keep it as close to real life as possible.) What is important about the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health (WCSDH) in Rio is that 125 nations pledged their commitment to work to promote awareness, develop policies, and support programs to transform certain social factors that play a significant role in determining whether or not a person will be healthy. The U. S. Centers for Disease Control uses the following words in an attempt to define ‘Social Determinants of Health’, “…complex, integrated, and overlapping social structures, and economic systems that are responsible for…” As you can see, we are already getting off into language that feels far removed from the daily realities of global health disparities like lack of access to care. Of course, all this has to do more with economics, education, and politics than with the common understanding of health and healthcare. And that is exactly the point. The fact that many high level political decision makers were present in Rio gives us some hope that there is a growing realization that health ministers alone cannot address these issues.

of Health. (Writing and discussions about social determinants of health can often get lost in very academic and sterile sounding language, so it is important to keep it as close to real life as possible.) What is important about the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health (WCSDH) in Rio is that 125 nations pledged their commitment to work to promote awareness, develop policies, and support programs to transform certain social factors that play a significant role in determining whether or not a person will be healthy. The U. S. Centers for Disease Control uses the following words in an attempt to define ‘Social Determinants of Health’, “…complex, integrated, and overlapping social structures, and economic systems that are responsible for…” As you can see, we are already getting off into language that feels far removed from the daily realities of global health disparities like lack of access to care. Of course, all this has to do more with economics, education, and politics than with the common understanding of health and healthcare. And that is exactly the point. The fact that many high level political decision makers were present in Rio gives us some hope that there is a growing realization that health ministers alone cannot address these issues.

The Rio Declaration referenced a similar conference in 1978 that produced The Declaration of Alma Ata, named for the Russian city –then in the USSR, where health was defined as “…a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease of infirmity… .” It went on to declare health as “a fundamental human right.” So we have known for a very long time that the goal of health for a nation and for the world is larger than healthcare, at least as we know it in the United States.

More than thirty years later, it is great to see the Spirit of Alma Ata is still alive. For, as economics, politics, and situational specifics change, it is imperative to remember that fundamental values and rights remain constant. It was right for Alma Ata to call for essential primary healthcare for all the world’s population back in 1978, and it is right for Rio to say today that just because we have not yet achieved the promise of Alma Ata does not mean that we should stop trying.

Progress is being made, but there is much more that can be done. That is why it is good to see the fresh eyes of students also present at the Rio conference. The International Federation of Medical Students (IFMSA) sent a delegation of ten medical students to Rio. Their take on the events of the WCSDH can be found on the IFMSA blog. While the IFMSA students don’t have the experience of some of the professionals who have been working at this for several decades, they do bring a fresh perspective and the ability to think more simply, with less jaded minds. In their critique, Renzo Guinto, the leader of the youth delegation, hits the nail on the head by saying: “The main problem of the Rio Declaration is that it failed to explicitly tell us how the unfair distribution of power, resources and wealth will be addressed, especially by Member States. The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health has been adamant about the need to tackle this lingering issue, as health inequities within and between countries are rooted in power relations and resource maldistribution. We understand that changing the current dynamics of power will not happen overnight. However, we believe that this Declaration could have been the watershed moment for leaders to make a strong commitment in making this world a fairer place.”

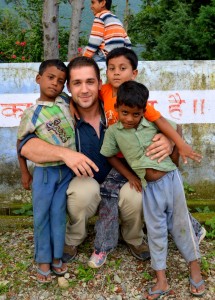

Students who participate in any of Child Family Health International’s (CFHI) Global Health Immersion Programs are, in fact, immersed into underserved communities around the world. They are mentored by local healthcare workers who face the challenges of few resources and many patients. Students say that they are deeply impacted as they see dramatic health disparities and the realities of the social determinats of health playing out right in front of their eyes. They become some of the most effective advocates for global health equity because they are eye witnesses to the consequences of inequity. And some of them are moved enough to have the experience directly impact their career plans, like Erin Newton who wrote about her experience on the Great Nonprofits Website. “Having never been exposed to the poverty, illness, and disease that I experienced in India, I learned so much about myself and found that I have a true passion for underserved and rural patient care. I learned that much of it can be prevented and I want to help treat these individuals and educate the rural communities as a future physician.”

Along with his challenges, Mr. Guinto also seems to speak for IFMSA in pledging to “…commit ourselves to continue engaging with all sectors involved in the work towards global health equity, spreading awareness of the social dimensions of health to our fellow young people, mobilizing them to take action in their respective communities and countries, doing our part, little by little, but with courage, constancy, and conviction.” We call on all CFHI alumni, whether they be part of IFMSA, AMSA (America), AMSA (Australia), ASDA, NSNA, SNMA, as well as many other groups, or just individual health science students, to read Mr. Guinto article and find the best way to engage in the great effort to achieve heath equity both at home and abroad.

With additional specific yet respectful challenges, Mr. Guinto offers an important contribution to the dialogues around social determinants of health that may require the veterans of this work to take a step back and refocus for a fresh look at what is taken for granted, or thought to be impossible. For it is only that kind of courage that will produce the bold steps needed to truly transform the status quo and bring about the promise of Alma Ata that is still waiting for us all.

of Health

of Health