For those who have participated in a service-learning trip abroad, you understand how life changing it can be. Visiting and learning from a community and culture different from your own can affect you in deep and meaningful ways. But programs and experiences vary widely. Some may claim opportunities for personal and professional growth, yet transparency and best practices are not always the reality on the ground. Also undermining quality, few programs provide true long-term benefits to the host community. One way that medical service-learning trips, or global health electives, can ensure quality is by applying a competency-based framework.

What is competency-based education?

Competency-based education (CBE) is not new, but the concept is receiving renewed attention in many fields, including global health and medical education. One distinguishing feature of CBE is that it begins with the end in mind. This means that the first priority when creating a competency-based curriculum is identifying the desired characteristics and qualities of a competent graduate. Once these characteristics are defined, they are broken down into building blocks, called competencies, which students master as they move through the curriculum. Unlike traditional education, competencies do not have to be course-specific or based on a specific number of course hours; instead, they integrate everything that the student is learning at a given time and build upon each other throughout their schooling. The amount of time required to master the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to achieve each competency may vary, but competence must be demonstrated before students are able to progress in the curriculum.

The beauty of CBE is that it is fluid and flexible, promoting critical application of the course material with a focus on what students should be able to do, as opposed to a singular emphasis on knowledge. The ability of CBE to produce graduates who are competent professionals has made the approach increasingly popular among various health fields. In fact, The Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH), the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), and the Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) have all developed core competencies for their programs.

Competency-based education in global health:

Over the past decade interest in global health has surged. Many health professions have integrated global health into their curriculum by applying a competency-based framework. The ASPPH created a Global Health Competency Model that builds on their established core competencies and the Joint US/Canadian Committee on Global Health Core Competencies established a set of six competencies for medical graduates. Even as competencies for global health education become more prevalent, little attention is being paid to global health electives (GHEs). This is puzzling considering GHEs are the primary way students gain experience in global health and in 2013, 30.2% of graduating medical students participated in a GHE.

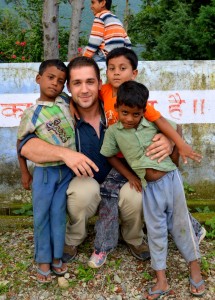

It is easy to understand why GHEs are increasing in popularity. GHEs provide benefits to students, improving cultural competence, strengthen clinical skills, and increased appreciation for prevention and providing care to the underserved. However, opportunities for growth are not always guaranteed as they are based entirely on program quality. Unfortunately, little effort has gone into determining the structure and educational objectives for GHEs. One way to ensure GHEs meet the needs of students and host communities is to apply a competency-based framework built around the health needs of the host community. Even though most GHEs take place in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), current global health competencies are primarily developed by professionals from high-income countries and little research has explored the effects of GHEs on local communities. In order to develop positive, reciprocal relationships with host communities, colleagues in LMICs need to be engaged in conversation to identify local health priorities and relevant competencies to address them. Students thinking about participating in a GHE can promote responsible global health education by choosing a program or organization, such as Child Family Health International, that has strong international partnerships and is dedicated to protecting the interests of host communities.

Bottom Line

Global health electives that promote cross-cultural partnerships and emphasize competencies addressing the health needs of the local community can provide incredible opportunities for personal and professional growth, while simultaneously offering benefits to the host community.

Special thanks to CFHI Intern, Emily December Latham, for authoring this blog.