This is the second of two guest blogs by Jessica Evert, MD, CFHI Medical Director, blogging from the CUGH Annual Meeting in Seattle. Be sure to leave a comment.

Ann Dower of University of Washington’s I-TECH Center said today “we must practice the art of partnership” in order to be successful in global health. Additionally, I was struck when Kevin De Cock MD, Director of the Center for Global Health at CDC, candidly reflected on his early career immersion experience in Nairobi, Kenya, saying, “I wish I was more humble.” I think this humility and the ability to form meaningful partnerships go hand-in-hand.

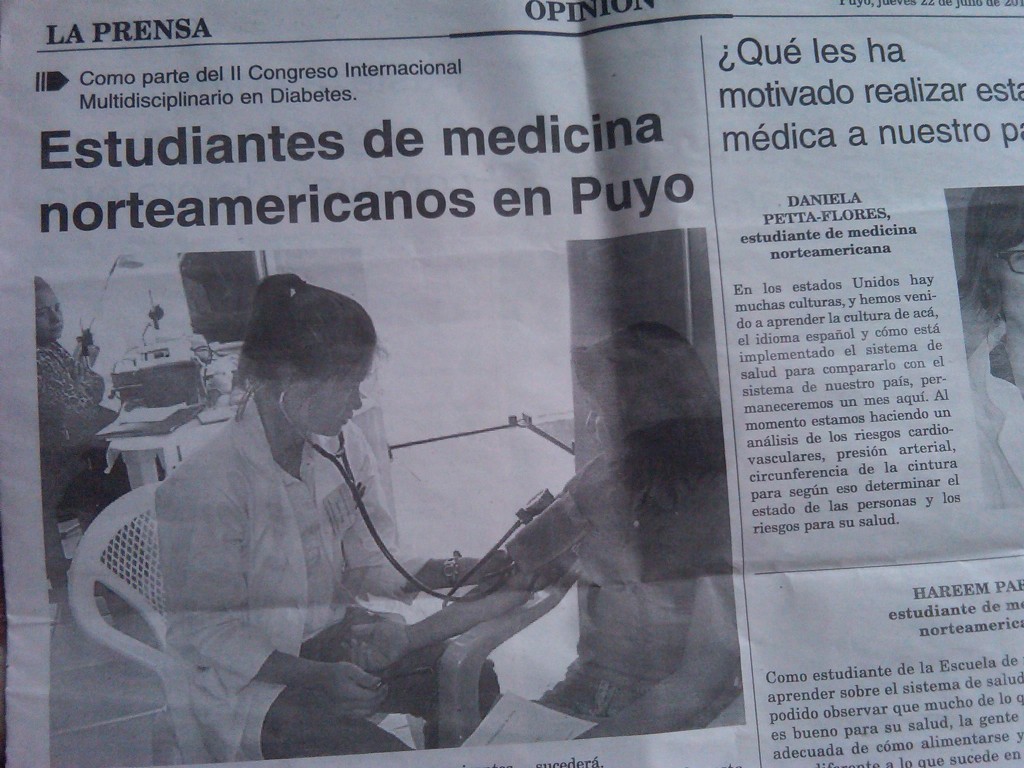

This idea of ‘partnership’ has come up countless times at the CUGH meeting over the last 2 days. Many seasoned global health experts have lamented over the lack of partnerships and failures of global health attempts due to this shortcoming. How can we learn from this history? How can we build training and educational programs that prioritize partnership? It seems that many times our process (the process of US based individuals, universities, and organizations) of global engagement is not necessarily the best approach to foster partnership or humility. We often have our own ideas of how to solve problems based on our views and our skills, rather than based on the voice of communities abroad. In academia, there is the nagging issue of faculty, and sometimes students, having to demonstrate personal accomplishments and quick outcomes which often trump the empowerment of communities to own the accomplishments and guide the outcomes. To find the answer to these important questions we need to look at how we frame introductory global health experiences for health science trainees (pre-health, medical, nursing, public health, allied health, dental, and other students) and how our academic institutions approach global engagement. The first experience abroad (a stepping stone experience) or first visit to a region or country is pivotal to frame how future global engagement occurs. If individuals go abroad and set-up a tent clinic outside the local healthcare infrastructure, an appreciation for local capacity, systems, and workforce is not realized. If students go to a hospital with faculty from their US institution who displace local physicians and assumes US clinical expertise translates immediately into similar expertise in an international setting, the student sees the glorification of US faculty, rather than the appreciation of unique practices, language, and expertise of local, native practitioners. It is time we recognize that the skills necessary for partnership need to be fostered from early levels of engagement and need to be modeled by our US teaching institutions and mentors.

How do we teach health science students and trainees about partnerships? What skills does partnership require? To delve into these questions, we must define partnership. The Partnering Initiative, an NGO that specializes in partnership training, defines partnership as follows: “a cross-sector collaboration in which organisations work together in a transparent, equitable and mutually beneficial way towards a sustainable development goal and where those defined as partners agree to commit resources and share the risks as well as the benefits associated with the partnership.” This is no simple task. They also define the partnering principles as follows- equity, transparency, mutual benefit. If partnership is fundamental to the success of global health activities, then we must judge global health activities in part based on these fundamental principles. The need for trust, mutual respect, and communication are presupposed in the process of building partnerships.

We can teach the principles and precursors to partnership through thoughtful global health immersion programs. I am proud to be a part of CFHI. I think CFHI is setting a standard for both academic and NGO based immersion programs. I liken CFHI immersion programs to participant-observation techniques I utilized during my thesis work. In anthropology the mechanism of understanding a culture, community, and executing research is participant-observation. Participant observation involves gaining an understanding of another social group or community, by inserting yourself into that community in a way that is agreeable to the community, while observing the practices and learning about the culture, social structure, systems, and other behaviors. CFHI immersion experiences provide an opportunity for participant-observation. I would argue that such participant-observation, done in the context of long-term CFHI partnerships, lay the groundwork and start fostering skills necessary to form meaningful partnerships with individuals and organizations abroad. The local health care providers are the experts who teach CFHI participants what their communities are facing. We have received feedback from partners that patients consider their local providers more capable because they are teaching western health science students (rather than Western physicians or students providing the expertise in patient care at the international setting). This dynamic is very important and very powerful. The first step in the cycle of partnership, as defined by The Partnering Institute, is “scoping.” In essence we are teaching our students and trainees how to scope, which includes listening, observing, and appreciating a local reality before trying to change it.

If partnerships are key to the success of global health programs and interventions, it is time we look at what it takes to impart the skills necessary to foster partnerships. These skills include observation, humility, and restraint so we can give voice to the local community and engage in truly mutually beneficial ways. By providing stepping stone global health immersion programs that prioritize the “scoping” necessary to form partnerships, we can engender a new generation of globally-active professionals who understand from early in their exposure and interaction with global communities the fundamentals of partnership and humility that Dr. De Cook and others wish they knew from the start. It reminds me of a quote by Nietzche, “When one has finished building one’s house, one suddenly realizes that in the process one has learned something that one really needed to know in the worst way – before one began.” We can provide these lessons before students build their proverbial global health houses through conscientious global health immersion.

Competency-based education (known as CBE) has been all the rage in medical education for nearly a decade. Competency in this realm has been described as the “habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and the community being served” Continue reading

Competency-based education (known as CBE) has been all the rage in medical education for nearly a decade. Competency in this realm has been described as the “habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and the community being served” Continue reading